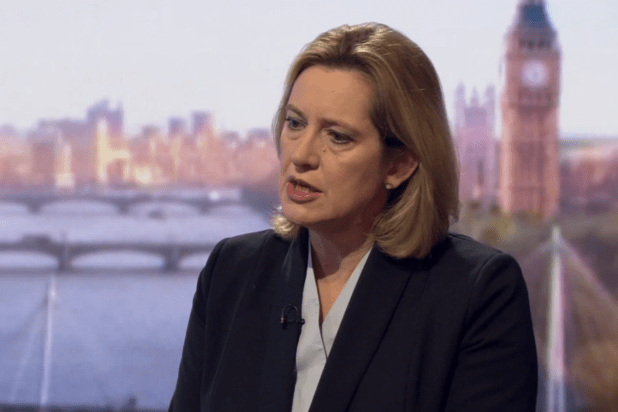

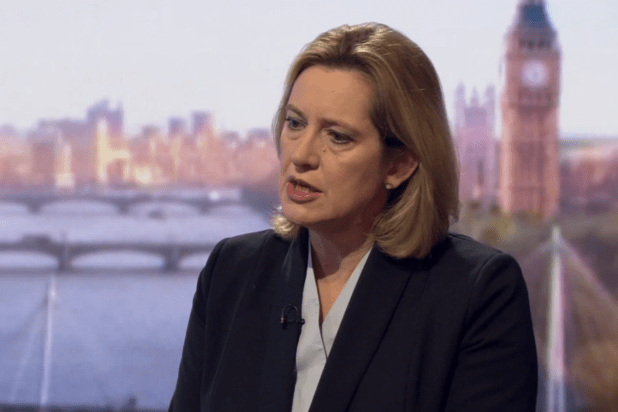

Yesterday UK government ministers once again called for social media companies to do more to combat terrorism. “There should be no place for terrorists to hide,” said Home Secretary Amber Rudd, speaking on the BBC’s Andrew Marr program.

Rudd’s comments followed the terrorist attack In London last week, in which lone attacker Khalid Masood drove a car into pedestrians walking over Westminster bridge before stabbing a policeman to death outside parliament.

Press reports of the police investigation have suggested Masood used the WhatsApp messaging app minutes before commencing the attack last Wednesday.

“We need to make sure that organisations like WhatsApp, and there are plenty of others like that, don’t provide a secret place for terrorists to communicate with each other,” Rudd told Marr. “It used to be that people would steam open envelopes or just listen in on phones when they wanted to find out what people were doing, legally, through warranty.

“But on this situation we need to make sure that our intelligence services have the ability to get into situations like encrypted WhatsApp.”

Rudd’s comments echo an earlier statement, made in January 2015, by then Prime Minister David Cameron, who argued there should not be any means of communication that “in extremis” cannot be read by the intelligence agencies.

Cameron’s comments followed the January 2015 terror attacks in Paris in which islamic extremist gunmen killed staff of the Charlie Hebdo satirical magazine and shoppers at a Jewish supermarket.

Safe to say, it’s become standard procedure for politicians to point the finger of blame at technology companies when a terror attack occurs — most obviously as this allows governments to spread the blame for counterterrorism failures.

Facebook, for instance, was criticized after a 2014 report by the UK Intelligence and Security Committee into the 2013 killing of solider Lee Rigby by two extremists who had very much been on the intelligence services’ radar. Yet the parliamentary ISC concluded the only “decisive” possibility for preventing the attack required the Internet company to have pro-actively identified and reported the threat — a suggestion that effectively outsources responsibility for counterterrorism to the commercial sector.

Writing in a national newspaper yesterday Rudd also called for social media companies to do more to tackle terrorism online. “We need the help of social media companies: the Googles, the Twitters, the Facebooks, of this world,” she wrote. “And the smaller ones, too — platforms like Telegram, WordPress and Justpaste.it.”

Rudd also said Google, Facebook and Twitter had been summoned to a meeting to discuss action over extremism, as well as suggesting the government is considering including new proposals to make Internet giants take down hate videos quicker in a forthcoming counterterrorism strategy — which would appear to mirror a push in Germany. The government there proposed a new law earlier this month to require social media firms to remove illegal hate speech faster.

So, whatever else it is, a terror attack is a politically opportune moment for governments to apply massively visible public pressure onto a sector known for engineering workarounds to extant regulation — as a power play to try to eke out greater cooperation going forward.

And US tech platform giants have long been under the public counterterrorism cosh in the UK — with the then head of intelligence agency GCHQ arguing, back in 2014, that their platforms had become the “command-and-control networks of choice for terrorists and criminals”, and calling for “a new deal between democratic governments and the technology companies in the area of protecting our citizens”.

“They cannot get away with saying… “

As is typically the case when governments talk about encryption, Rudd’s comments to Marr are contradictory — so on the one hand she’s making the apparently timeless call for tech firms to break encryption and backdoor their services. Yet when pressed on the specifics she also appears to claim she’s not calling for that at all, telling Marr: “We don’t want to open up, we don’t want to go into the cloud and do all sorts of things like that, but we do want [technology companies] to recognise that they have a responsibility to engage with government, to engage with law enforcement agencies when there is a terrorist situation.

“We would do it all through the carefully thought through, legally covered arrangements. But they cannot get away with saying ‘we are in a different situation’ — they are not.”

So, really, the core of her demand is closer co-operation between tech firms and government. And the not so subtle subtext is: ‘we’d prefer you didn’t use end-to-end encryption by default’.

After all, what better way to workaround e2e encryption than to pressurize companies not to pro-actively push its use in the first place… (So even if one potential target’s messages are robustly encrypted, the agencies could hope to find one of their contacts whose messages are still accessible.)

A key factor informing this political power play is undoubtedly the huge popularity of some of the technology services being targeted. Messaging app WhatApp has more than a billion active users, for example.

Banning popular tech services would not only likely be technically futile, but any attempt to outlaw mainstream networks would be tantamount to political suicide — hence governments feeling the need to wage a hearts and minds PR war every time there’s another terrorist outrage. The mission is to try to put tech firms on the back foot by turning public opinion against them. (Oftentimes, a goal aided and abetted by sections of the mainstream UK media, it must be said.)

In recent years, some tech companies with very large user-bases have also been shown to make high profile stances championing user privacy — which inexorable sets them on a collision course with governments’ national security priorities.

Consider how Apple and WhatsApp have recently challenged law enforcement authorities’ demands to weaken their security system and/or access encrypted data, for instance.

Apple most visibly in the case of the San Bernardino terrorist’s locked iPhone — where the Cupertino company resisted a demand by the FBI that it write a new version of its OS to weaken the security of the device so it could be unlocked. (In the event, the FBI paid a third party organization for a hacking tool that apparently enabled it to unlock the device.)

While WhatsApp — aside from the fact the messaging giant has rolled out end-to-end encryption across its entire platform, thereby vastly lowering the barrier to entry to the tech for mainstream consumers — has continued resisting police demands for encrypted data, such as in Brazil, where the service has been blocked several times as a result, on judges’ orders.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the legislative push in recent years has been to expand the investigatory capabilities of domestic intelligence agencies — with counterterrorism the broad-brush justification for this push to normalize mass surveillance.

The current government rubberstamped the hugely controversial Investigatory Powers Act at the back end of last year — which puts intrusive powers that had been used previously, without necessary being avowed to parliament and authorized via an antiquated legislative patchwork, on a firmer legal footing — including cementing a series of so-called “bulk” (i.e. non-targeted) powers at the heart of the UK surveillance state, such as the ability to hack into multiple devices/services under a single warrant.

So the really big irony of Rudd’s comments is that the government has already afforded itself swingeing investigatory powers — even including the ability to require companies to decrypt data, limit the use of end-to-end encryption and backdoor services on warranted request. (And that before you even consider how much intel can profitably be gleaned by intelligence agencies looking at metadata — which end-to-end encryption does not lock behind an impenetrable wall.)

Which begs the question why Rudd is seemingly asking tech companies for something her government has already legislated to be able to demand.

” …stop this stuff even being put up”

Part of this might be down to intelligence agencies being worried that it’s getting harder (and/or more resource intensive) for them to prioritize subjects of interest because the more widespread use of end-to-end encryption means they can’t as easily access and read messages of potential suspects. Instead they might have to directly hack an individual’s device, for instance, which they have legal powers to do should they obtain the necessary warrant.

And it’s undoubtedly true that agencies’ use of bulk collection methods means they are systematically amassing more and more data which needs to be sifted through to identify possible targets.

So the UK government might be testing the water to make a fresh case on the agencies’ behalf — to push for quashing the rise of e2e encryption. (And it’s clear that at least some sections of the Conservative party do not have the faintest idea of how encryption works.) But, well, good luck with that!

Either way, this is certainly a PR war. And — perhaps most likely — one in which the UK government is jockeying for position to slap social media companies with additional extremist-countering measures, as Rudd has hinted are in the works.

Something that, while controversial, is likely to be less so than trying to ban certain popular apps outright, or forcibly outlaw the use of end-to-end encryption.

On taking action against extremist content online, Rudd told Marr the best people to solve the problem are those “who understand the technology, who understand the necessary hashtags to stop this stuff even being put up”. Which suggests the government is considering asking for more pre-emptive screening and blocking of content. Ergo, some form of keyword censoring.

One possible scenario might be that when a user tries to post a tweet containing a blacklisted keyword they are blocked from doing so until the offending keyword is removed.

Security researcher, and former Facebook employee, Alec Muffett wasted no time branding this hashtag concept “chilling” censorship…

But mainstream users might well be a lot more supportive of proactive and visible action to try to suppress the spread of extremist material online (however misguided such an approach might be). The fact Rudd is even talking in these terms suggests the government thinks it’s a PR battle they could win.

We reached out to Google, Facebook and Twitter to ask for a response to Rudd’s comments. Google declined to comment, and Twitter had not responded to our questions at the time of writing.

Facebook provided a WhatsApp statement, in which a spokesperson said the company is “horrified by the attack carried out in London earlier this week and are cooperating with law enforcement as they continue their investigations”. But did not immediately provide a Facebook-specific response to being summoned by the UK government for discussions about tackling online extremism.

The company has recently been facing renewed criticism in the UK for how it handles complaints relating to child safety. As well as ongoing concerns in multiple countries about how fake news spreads across its platform. On the latter issue, it’s been working with third party fact checking organizations to flag disputed content in certain regions. While on the issue of illegal hate speech in Germany Facebook has said it is increasing the number of people working on reviewing content in the country, and claims to be “committed to working with the government and our partners to address this societal issue”.

It seems highly likely the social media giant will soon have a fresh set of political demands on its plate. And that ‘humanitarian manifesto‘ Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg penned in February, in which he publicly grappled with some of the societal concerns the platform is sparking, is already looking in need of an update.